If you haven't already devoured them, here are parts one, two, and three.

How long a campaign will keep—and how to keep it fresh.

Ad campaigns are like potatoes. Some are like McDonald’s fries—irresistible when they’re fresh, but inedible shortly thereafter. Others are like vodka. They can last for years. But most are like a regular old bag of russets. Properly packaged and placed, they’ll stay good for several weeks, sometimes even months.

Enjoy responsibly.

Enjoy responsibly.

Just to be absolutely clear (like a good vodka), when we say “campaign,” we simply mean a coordinated series of ads that show up in different formats and places, but share the same core message, appearance, and goal.

That goal is particularly vital and central. Since we’ve got this potato theme going, think of the goal as the campaign’s root. It’s what you’re wanting to grow—be that the sales of just one product or the image of your entire brand. The ads are all offshoots of the root goal, and they go back to it.

With taters, the root determines not just what’s growing, but how long it takes. Similarly, there’s a definite connection between a campaign’s goal and duration. Admittedly, it’s not a simple 1:1 relationship, but still, some goals lend themselves to shorter, seasonal campaigns while others can be annuals or perennials.

To unearth some insights on this, let’s look at three common campaign goals through the eyes of ProTatoes—a superior, but spurious spud farm.

Goal 1: Grow a Single Product (or any one thing—a service, offer, opportunity, etc.)

Product campaigns like the one shown above are the meat and...(wait for it) potatoes of the ad industry. Advertisers feed us one after another, and once we’ve had too much, they offer us a Diet Coke or some Zantac.

Even though we’re served ads for lots of different things, each of them directs our attention to just one offer, then calls us to action. Being concentrated on one thing makes these ads work, but it also makes them go bad or stale the faster than other types of campaigns.

Case in point, purple yams. No matter how pretty or healthy they are, we’ll get fed up if they’re served for breakfast, lunch, and dinner indefinitely. That’s why product campaigns like this often last just six to eight weeks. Past that, they lose flavor and favor.

And that’s okay. ProTatoes has other crops to promote and doesn’t want to keep advertising the same thing year-round. But what if they did? What if growing the sales of purple yams was a top long term goal? Then they’d have to either repackage the entire campaign or refresh the individual ads on a regular basis.

No one does that better (or weirder) than Geico. For two decades, they’ve constantly come up with new ways to say the same thing: 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on car insurance. All together, their ads are a funky, mixed-up soup—but one that’s fresh, flavorful, and unforgettable.

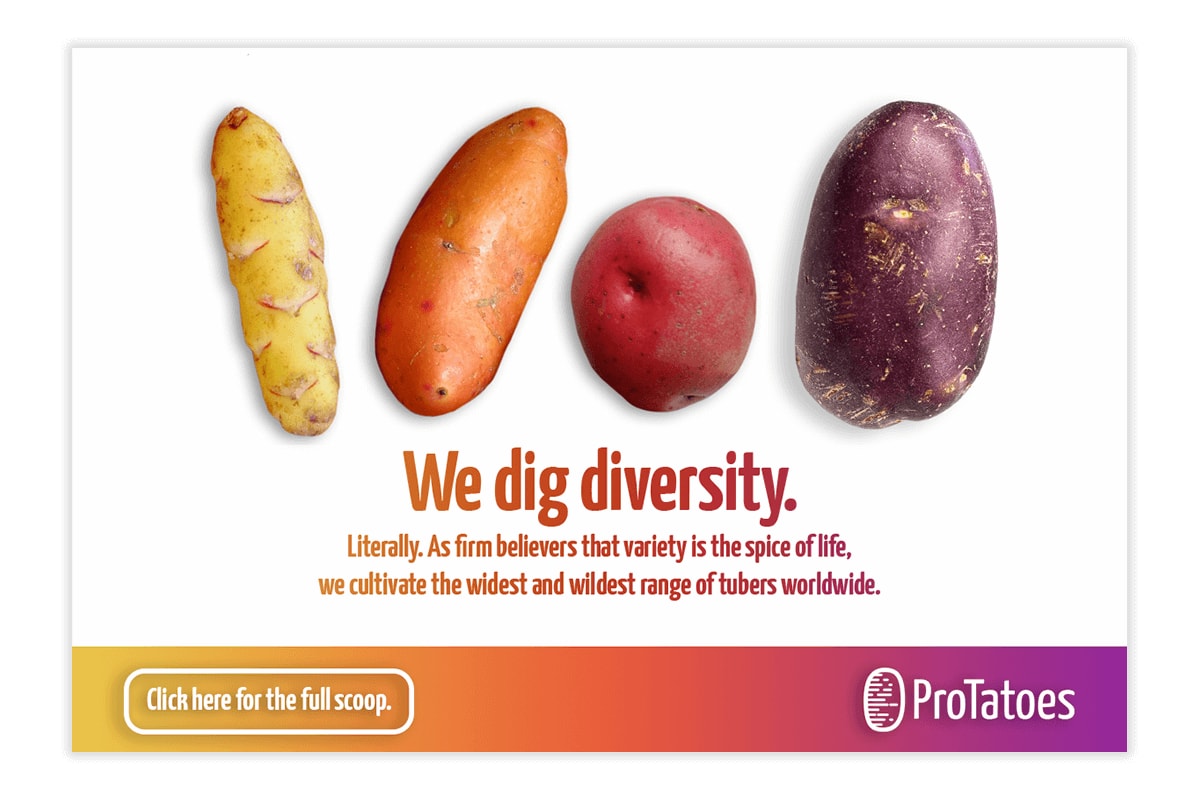

Goal 2: Grow Multiple Products

Besides promoting individual crops, ProTatoes does some “range advertising,” so called because it includes a range of products. It offers several advantages:

- The ability to show off a wider field of expertise

- The possibility of cross-pollination—letting one product stimulate the growth of another

- The opportunity to appeal to a broader customer base with different tastes

In some ways, it’s like a buffet...or a Taco Bell/KFC/Pizza Hut. They offer all you can eat in one location, so why go anywhere else? When ordering, just remember to get Diet Pepsi (they don’t have Coke) and pop a Zantac.

Another advantage of range advertising is that it has the potential to last longer than single product advertising. ProTatoes could essentially rotate their crops—marketing them all, but giving special attention to each in turn over the course of the campaign.

This rotation can preserve freshness, but for how long? That depends entirely on the number of crops featured, their individual merits, and their combined market appeal. ProTatoes has to monitor progress along the way (like we discussed in the previous article) and rotate the ads or the entire campaign when they see it’s fully ripe and heading for rot.

Goal 3: Grow a Producer

Sometimes the goal isn’t to promote the product, but the producer. The brand. That’s what ProTatoes is aiming for. They want to grow not just sales, but their image as the cutting edge grower of the biggest variety of healthy organic potatoes.

For a real life example, don’t think potatoes, but apples. Or rather, Apple and its “Get a Mac” campaign. This is iconic brand advertising—and ironic, too, since it was technically a product campaign for the Macintosh, not a brand campaign for Apple. Even so, it took on a life of its own and came to embody the whole Apple persona in the cool, collected character of Justin Long—as opposed to the nerdy, bumbling PC.

A brand campaign like this can typically outlast product campaigns because it’s selling something more substantial and deeply rooted—not the company’s latest product, but its lasting identity. The who behind the what. “Get a Mac” spanned four years and featured 66 commercials even while promotions for other products like the iPhone and iPod came and went.

While this illustrates the potential lasting power of brand advertising, it also brings up a common strand that’s connected all three campaign types—the need to refresh or replace individual ads. “Get Mac” could last four years because it was 66 commercials, not the same one running continually and wearing out.

So regardless of the overall campaign goal and length, each ad in it has a limited shelf life. That’s our next topic.

Ad Shelf Life and Half Life

If you’ve heard the old adage that customers need to see an ad seven times before it’s effective, you can forget it. As Andy Brice discovered, the so-called “advertising rule of 7” is a steaming pile of bologna. Or not. Because cooked bologna is actually quite tasty.

This rule of 7 (which is no rule at all) has been used to justify running the same ads for a long time so customers will finally absorb and act on them. But actual research indicates prolonged exposure has the opposite effect—that ads lose steam and flavor each time they’re served up. It’s the law of diminishing returns, or what’s known as “adstock decay” in media measurement.

For our purposes, we can think of it as an ad’s shelf life, except it’s not determined by a simple expiration date. Instead, like radioactive decay, advertising shelf life is measured in half lives—the time it takes for an ad to lose half of its potency.

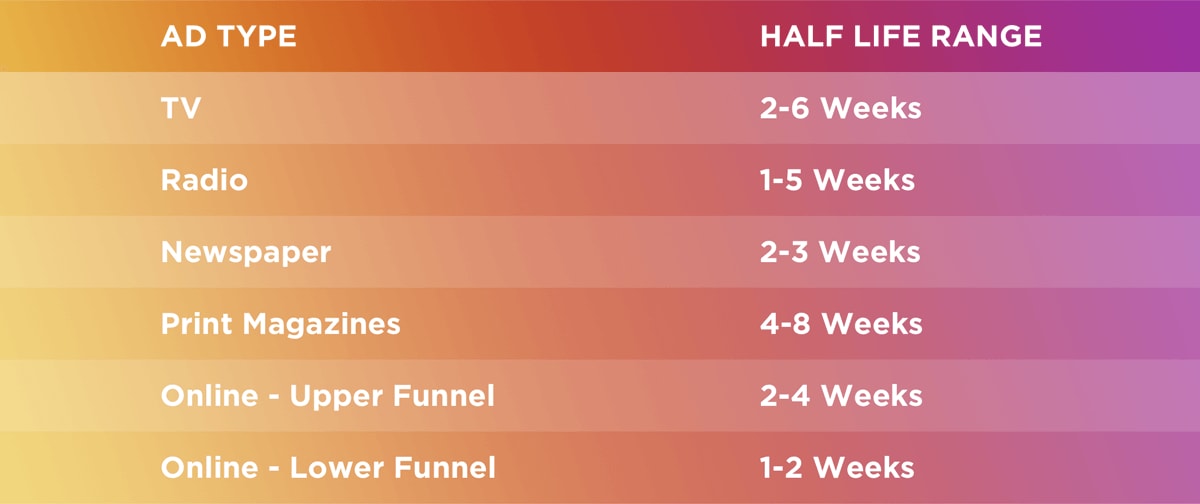

Not surprisingly, you’ll find differing opinions and calculations on the subject, but the clearest, real-world guidelines we’ve found come from Steve Kerho in his Fast Company article “How Long Does Your Ad Have an Impact?”.

Based on a wide data set from several industries, Steve’s company established the following benchmarks for ad half lives.

NOTE: Upper funnel means ads delivered to a general audience on a high-traffic web page. Lower funnel means ads targeted to specific people in the market for what you’re selling.

NOTE: Upper funnel means ads delivered to a general audience on a high-traffic web page. Lower funnel means ads targeted to specific people in the market for what you’re selling.

Upper funnel ads outlast their lower funnel counterparts because they’re seen by more total people and more uninitiated people—those who weren’t previously aware of the offer. Typically, the fewer, but more targeted recipients of lower funnel ads are already product-aware, and they’ll either immediately act on or ignore the ad.

Before jumping to conclusions or applications, we should ask, “Why such differences between and within each category?” There are many reasons.

- First, we’re not looking at homogenized results. These decay rates are based on a variety of different ads, products, industries, and target audiences. We shouldn’t be surprised to find irregularities in that kind of salmagundi.

- Second, some ads are more flavorful than others. Think 30-second TV commercial vs. static web banner. No matter how good the banner is, it can’t compete with video, audio, and the full storytelling power of a commercial.

- Third, you can’t know exactly when some ads will be consumed. TV, radio, and especially, magazines fall into this category. They’re harder to track. There’s no running count of clicks or impressions. You know when ad goes out, but not when someone will see or act on it. A patient at the dentist may pick up a magazine five months from now, see an ad, and decide to buy.

- Fourth, the ingredient quality varies. Excellently prepared and packaged ads will outlast their generic or half-baked counterparts. Like we’ve said before, there’s no substitute for grade A content.

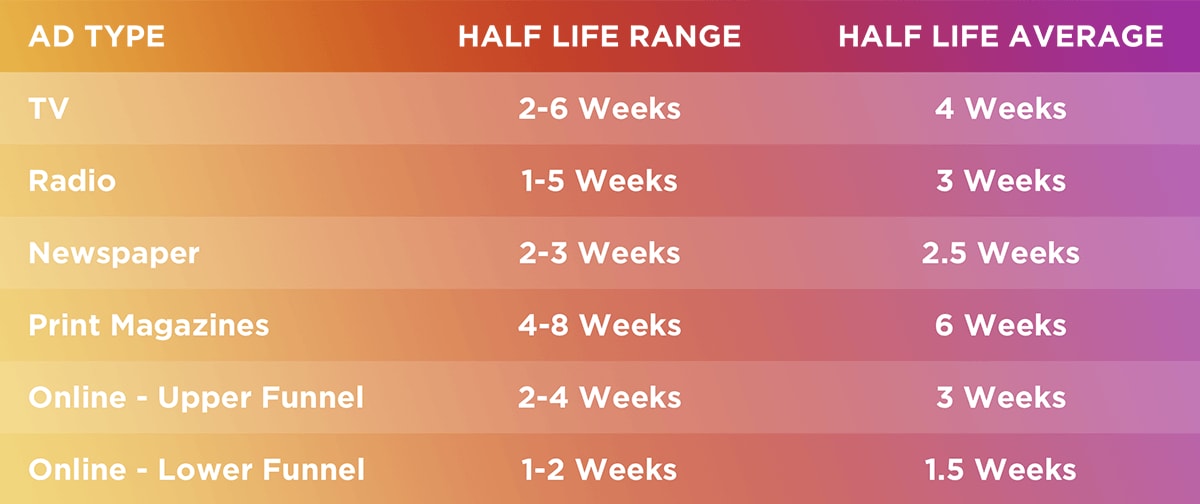

Even with those issues and variations, Steve’s half life benchmarks give us a good starting point for determining how long our ads will keep. If we begin by figuring the average decay rate for each ad type, here’s what we get.

Based on those averages, we can estimate that the typical shelf life of a campaign is six to eight weeks. Clearly that measurement isn’t set in stone—set in jello, maybe—but after that long, every ad type except magazines has lost 3/4 or more of its potency, and even magazines have lost over half.

So as a rule of thumb, campaigns expire after six to eight weeks, but some ads in those campaigns expire even faster—especially those online. So how do we get ads with shorter shelf lives to last to the end of a campaign? Simple. We introduce new ingredients or substitutes.

Like Geico, we can cook up different flavors and variations of the same basic idea, and it doesn’t have to be a grueling process. Sometimes it’s as easy as rewording a headline or replacing an image. The key is to keep some fresh ingredients in what you’re serving up.

Again, as any good recipe will tell you, your own cook times will vary. The measurements we’ve provided are a baseline, but you’ll need to regularly monitor and make adjustments as you go. That brings us our final point—not just of this article, but the whole series.

Measuring like a chef is no cakewalk.

After four helpings of the subject, that much should be plain—perhaps even painful considering the the portion sizes of information and work involved. If that’s the case, know we can relate. Really. Even after doing this for years, peeling back all the layers of ad measurement can sometimes still bring a tear to the eye.

That’s to be expected, especially when you’re first starting out, but don’t let it discourage you. No one becomes a head chef or expert advertiser (if there is such a thing) overnight. With time and practice, you can master this skill.

And for anyone who’s convinced they really can’t measure up, we’d still say not to give up. If you can’t stand the heat, don’t get out of the kitchen. Just get someone to join you. We’d be glad to come alongside and prepare something great together.