That sounds like the title of a Bond flick.

One with a sinister but speechless villain who would likely spell doom for 007. Because when he’s inevitably captured, it’s always the bad guy’s long, revealing monologue that gives Bond the time to escape and the intel to avert disaster.

No monologue. No escape. No more Bond.

Saying nothing kills 007—but it also kills advertising. (See how we segued there?) It’s not that ads are speechless—far from it—but they’re infamous for making empty or abstract claims that really say nothing. In truck driver recruiting (where we spend a lot of time), we see lots of job ads with empty words. And to stick with our theme, here are 007 examples of nothings we should never say again. Even if you’re not in the trucking world, you can adapt and apply the lessons here to your own business.

001. Great

What’s wrong with great? Nothing if it’s truly great, but it’s probably not. Remember, "great" means considerably above average and out of the ordinary. So we can legitimately say that Bond is a great agent, but probably can’t say the same of our product, service, or job.

Is our “great compensation” or “great health coverage” remarkably better than the next company’s? They might be good—or even better—but great? Not likely.

Besides that, "great" isn’t such a great description. It says something is exceptional, but doesn’t say how or why. If you’re gonna claim greatness, you’ve gotta be ready to back it up with facts and reasons. And in that case, why not skip the word "great" and just get straight to the facts and reasons?

Instead of saying “great pay,” give the actual amount—a million bucks an hour or whatever. And even if it’s not that great, just say what it is. Give people the facts, and let them decide. Other words or descriptions similar to great are best, top, #1, most, and industry-leading. And the greatest thing to do with all of these words is to remove and replace them with the straight facts.

002. Up To

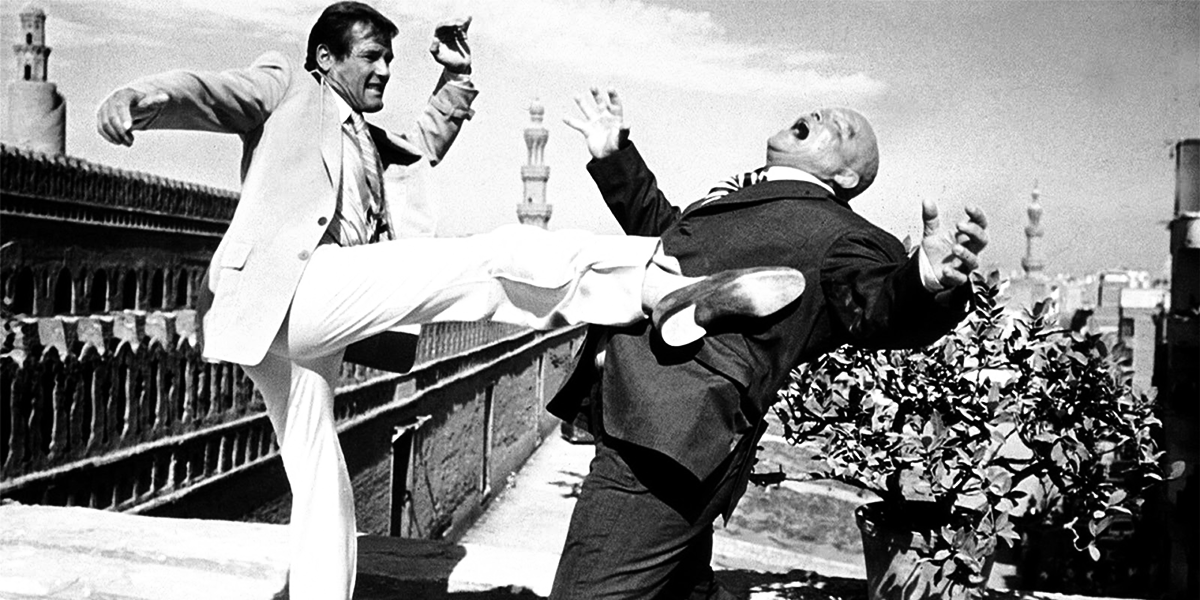

Emilio Lago and Ernst Blofeld are definitely up to something.

Emilio Lago and Ernst Blofeld are definitely up to something.

Up to is up to something. It’s suspicious. Like an eyepatch or a scar down the cheek. When a job ad says, “Earn up to $70,000,” we know it’s giving the best-case scenario. And we want to know the worst case or, at least, the typical case.

And that’s really our advice here: don’t use "up to" unless you also balance it out with realistic expectations.

Potential to earn up to $70,000. Average income of $55,000.

See how that reduces suspicion and adds to credibility? It’s up to you to do it.

003. Competitive

006 vs. 007. Highly competitive.

006 vs. 007. Highly competitive.

When an ad describes something as “competitive”—pay, benefits, whatever—we understand what the company's trying to say:

- We're as good as the next guy.

- We’re in the running.

- We’re not lagging behind.

We get the idea, but there are at least two problems.

First, you can’t just describe something as competitive. You have to demonstrate it. So, instead of saying, “Our health insurance is really competitive,” you’ve gotta show its strengths—premiums, deductibles, out-of-pockets, and so on. If they really are competitive, people will come to that conclusion on their own.

Second, competitive doesn’t mean you’re a winner. It just means you have a fighting chance. That’s good. We want to be competitive and competent in as many areas as possible, but what’s better is to promote where we have a real advantage over competitors. That turns us from fighters to victors.

004. State of the Art

Let’s be honest with ourselves, unless Q (or Elon Musk) designed our tech, it’s not the world’s most advanced—but we see lots of trucking job ads saying so:

- Top-of-the-line equipment

- Cutting-edge technology

- Newest fleet on the road

By themselves, those statements sound empty and exaggerated because the real proof is in the spec sheets. "State of the art" and similar descriptions lack accuracy and detail, which are both crucial when communicating anything tech-related. So for trucking companies, it would be far better to say something like,

We’ve upgraded our whole fleet to 2017 Mack Anthem trucks.

That gives us real features: make, model, and age.

Specific features matter, but benefits matter more. We have to help people understand how a feature works in their favor. We could do that lots of ways with the Anthem truck. For example, if our company pays a fuel efficiency bonus (like many companies do), we could say:

Driving an Anthem, you’ll have better aerodynamics and fuel economy, making it easier to earn bonuses for conserving fuel.

See the difference it makes to explain not just the what, but also the so what.

005. !!! and ALL CAPS

YOUR AD IS NOT A FIGHT SCENE! And exclamation points won’t up the action, so be a good agent and eliminate them.

This isn’t just a grammar issue. In fact, it’s not mainly a grammar issue. It’s a messaging issue. We need to write ads and choose words that are strong enough to stand on their own—without needing to be propped up by caps lock or shift + 1. For example:

Don't Say: $$ PAY RAISE!!

Do Say: We've raised driver pay by $2,500.

See how the second option, simple as it is, has enough punch by itself.

006. Family

Bond's family estate, Skyfall Lodge

Bond's family estate, Skyfall Lodge

Bond was orphaned as a child and, figuratively speaking, was adopted by the Crown—giving himself to Her Majesty’s Secret Service. His work may have served as a surrogate family, but the recipients of our ads probably (hopefully) aren’t looking for that same kind of relationship with us.

Yet job ads often promote family bonds:

- We’re a family company.

- Our employees are family.

- Come join our family.

The intent behind these statements is to portray the business as personal. Relational. Human. Not a cold, calculating cash register. Not a bunch of heartless taskmasters. That’s all good, but it’s not the same as being a family. Not by a long shot.

Work, we choose. Family, we don’t. We’re born into it and can’t get fired for not showing up. Family focuses on who we are. Work focuses on what we do. And when we get together with colleagues, it’s not to have a reunion, but to accomplish a job. It’s the work that binds employees together, not family ties.

While working together, we can still treat one another right. Be fair. Kind. Helpful. Friends even. But that doesn’t make a family. It just makes a good workplace. And that’s the whole point here. We should promote what makes us a good workplace. We shouldn’t try to pass that off as family time.

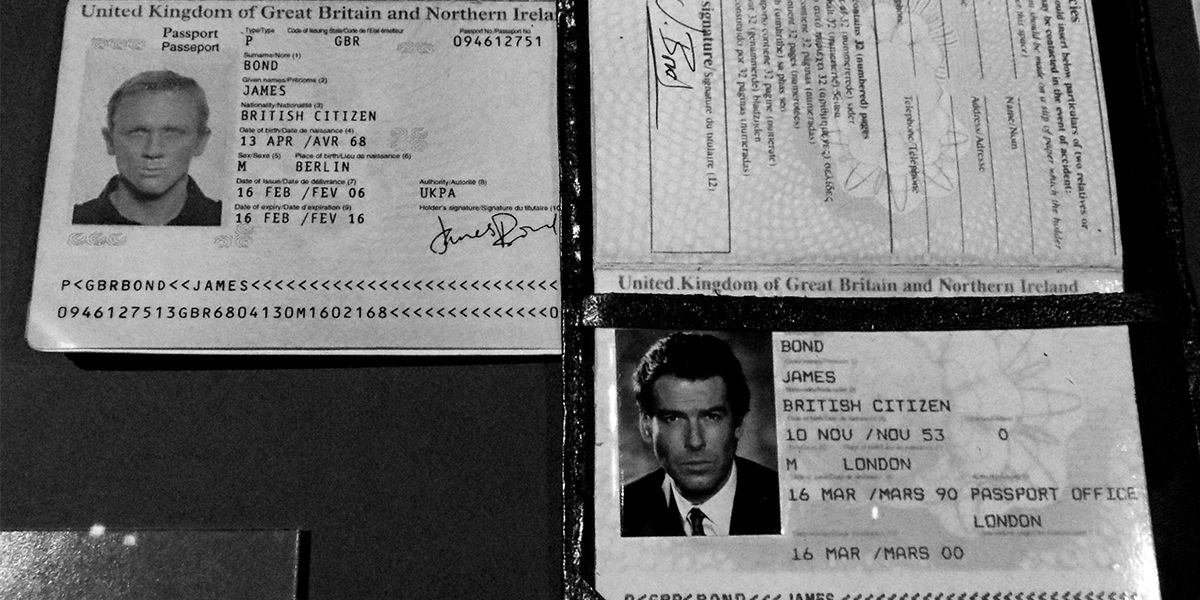

007. A Name, not a Number

If intelligence agencies recruited like trucking companies, they’d produce testimonial videos where at least one of the spies interviewed would say:

In all my previous jobs and missions, people only called me by code names—XXX, Alpha Wolf, or TK-421. But not here. At this agency, I’m a name, not a number.

This claim of knowing employees personally by name, instead of impersonally by number, is everywhere in the trucking industry (where drivers are often identified by their truck number). It’s rare to find a job ad, webpage, or video that doesn’t say it—meaning it's a cliche, an expression that’s overused and lacks original thought. That makes it high time to retire “not a number” and recast it.

The Bond franchise does that every decade or so. It brings in new blood to reinvigorate the role. Along with keeping the character current, each successive actor imparts his own originality. That's what we need to do with our recruiting message, especially as it concerns this name, not number idea. Just like Bond isn't simply Bond (he's a whole series of different people), so a driver isn't simply a driver. Each one is unique and has his own story.

It's our job to tell those stories. If our company is a place that values drivers and that drivers value, then we need to show those real drivers with real stories and examples that support our claim to support them. Imagine if they shared stories like,

When I was injured and laid up in the hospital, my driver manager, Jake, came and spent the evening with me. And Carol and Terry in the office took meals to my wife and kids. Knowing that my company doesn't just care when I'm on the road, but also off of it—and knowing they care about my family, too—that means everything.